As I have translated Friedrich Bauer’s accounts of the histories of Berlin-based typefoundries, I have been adding too much commentary. That is quite visible in my previous two entries. At this pace, who knows when I will have gotten through the entire book! To speed the project along somewhat, I have compiled my translations of nine foundry entries into this post.

Almost all deserve more commentary than I have added here, especially the largest two firms: Eduard Haenel and Ferdinand Theinhardt’s. Haenel’s foundry, for instance, was probably the most important German foundry of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, Friedrich Bauer’s chronicles do not provide tremendous details about its history. Even in the first edition of his Chronik, published when the firm was still active, it received less space than its then-larger contemporaries, like H. Berthold. By the time Bauer’s second edition appeared, the foundry had been closed for longer than a decade.

Haenel and especially Theinhardt’s foundry are well represented elsewhere on this site. Indeed, over the last six years, Theinhardt has been something of a patron saint for this site. His work is addressed in several posts, accessible via the keyword Theinhardt.

Bauer’s accounts of the Haenel foundry did not mention a single type specimen. Considering the volume of mid-century specimens that Haenel and his successors printed, that seems quite an unfortunate oversight. Most of the specimens that the firm must have published after its move to Berlin from Magdeburg were digitized a few years ago. Here is a list of well-digitized copies. I have left off unsatisfactory “Google Books” digitizations:

- The best place to start is with a large volume of specimen sheets. The foundry’s last owner, Alexander Jürst, donated it to the library of Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum in 1906. Its title page states that it contains everything the foundry had produced “up to that point.” Nevertheless, I think that the year of the volume’s binding was closer to 1896 than 1906 and that the foundry’s later works were not included.

- A lovely set of polychromatic ornaments printed before the move to Berlin

- An undated collection of a few Haenel specimen sheets from Günter Gerhard Lange’s collection

- A specimen of polychromatic ornaments and borders printed before 1864

- Another circa 1864 collection of borders

- The wonderful hard-bound catalog from 1891.

- A volume of specimen sheets misdated to 1918, but surely bound before 1896

- A catalog bound after 1896, which Berlin’s Kunstbibliothek catalogs as being from 1902.

- A circa 1900 brochure

- A brochure with the same cover, cataloged by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin in 1915 but not printed that late. It is followed by four other brochures, none of which are as late as their 1915 cataloging date.

- Four later brochures, printed before 1915.

- A specimen of new typefaces, from either around 1902 or around 1912

- A circa 1912 catalog

The text below – save for image captions and notes – is my translation of pages 20 to 24 of Friedrich Bauer’s Chronik der Schriftgiessereien in Deutschland und den deutschsprachigen Nachbarländern. It was published in 1918 by the Verlag des Vereins Deutscher Schriftgießereien, whose headquarters was then in Offenbach am Main.

Lehmann & Mohr – Assmann

1834

E. Ludwig Lehmann and Karl Wilhelm Mohr purchased a subsidiary foundry from Dreier & Rost-Fingerlin in Frankfurt am Main that operated in Hamburg under the direction of Christian Reinheimer on 1 August 1834. They transferred it to Berlin and renamed the company Lehmann & Mohr. Mohr had previously worked at Dresler & Rost-Fingerlin for seven years.

1835

In 1835, the company published a specimen for a verschobene Egyptienne.[1] It was later followed by specimens for display typefaces and vignettes.

1838

A subsidiary in Litoměřice, Bohemia was established in 1838 and called Medau, Lehmann & Mohr.

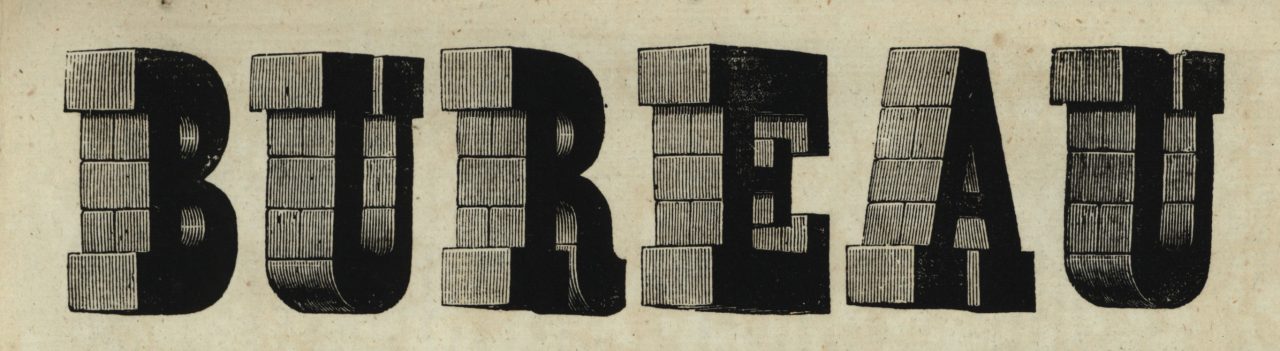

A “verschobene Egyptienne” from the Proben der vorzüglicheren Schriftensorten, nebst Einfassungen, Vignetten und Guilloche-Verzierungen, aus der Buchdruckerei des F. Gastl (Brno, 1844) [link]. I don’t know the source of Gastl’s type and do not expect that it came from Medau, Lehmann & Mohr. However, these letters illustrate what that foundry’s “verschobene Egyptienne” might have looked like.

1853

On 1 Januar 1853, sole ownership of the “Typefoundry and und Stereotypists managed for joint account since 1834”[2] was transferred to K. W. Mohr, who continued to operate it under its old name.

The foundry operated with just one casting furnace in 1854.

1873

W. Ohm Jr. purchased the Lehmann & Mohr typefoundry on 10 January 183. It continued to operate under the name Lehmann & Mohr (W. Ohm jr.). The foundry later continued under the name F. W. Assmann in Berlin. Since 1870, F. W. Assmann had been the owner of the typecasting machine factory that the punchcutter C. Kisch had established in 1847. That was the first independent casting-machine manufacturer in Germany. Lehmann & Mohr had purchased its first machine. After Assmann purchased the foundry, he gave up the manufacturing of casting machines.[3]

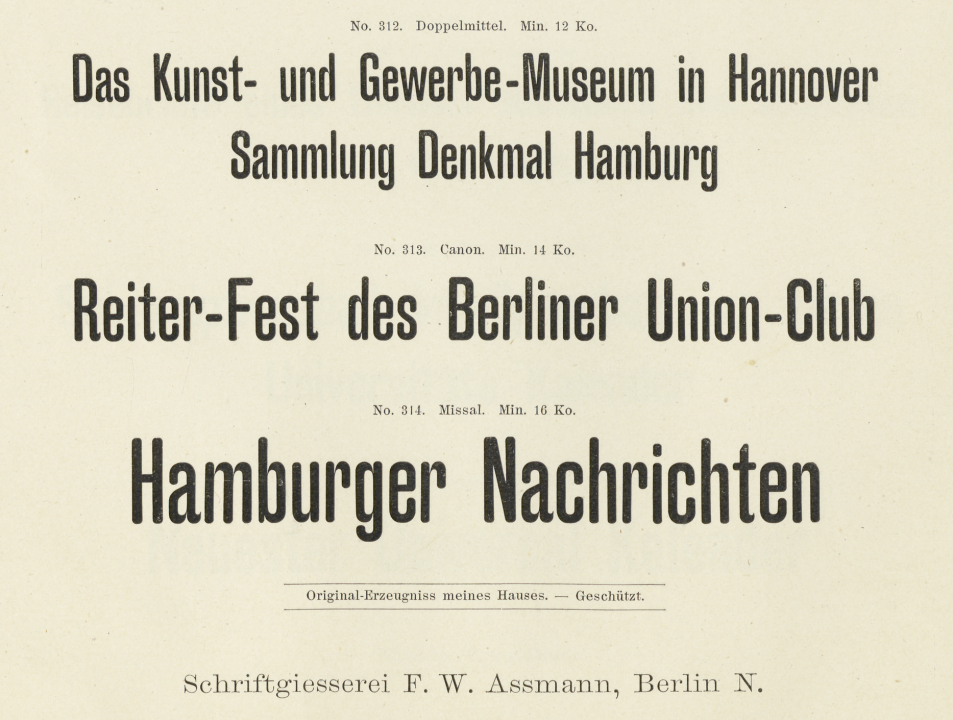

Above, you can see the three largest sizes of Schmale runde Grotesk, a condensed rounded sans created at the F. W. Assmann foundry in Berlin, probably during the mid-1880s. In the 1890s, when H. Berthold began casting type, it acquired matrices for the typeface. An internal Berthold notebook indicates that its Schmale rund Grotesk came from the Assmann foundry. Nevertheless, its specimens for the types, like this one, claimed that they had originated in house – a falsity for which I have no explanation to offer. Rounded sans serifs were probably the most popular Grotesk variety in Germany during the 1880s.

1899

F. W. Assmann died in 1899. The business was continued on his widow’s account by Georg Schmedes.

1915

On 31 December 1914, the company ceased operations. The foundry was purchased by Gebr. Klingspor in Offenbach am Main on 1 February 1915 and dissolved.

Haenel – Gronau

1838

Eduard Haenel (born 1804) moved the typefoundry he had founded in 1830 from Magdeburg to Berlin after a 1 May 1838 fire destroyed the Haenel Court Printing House, which had been established in 1731. At first, Lützowerwegstraße 44 was the Berlin location of the foundry, then Lützowerwegstraße 9. In conjunction with the typefoundry, Haenel also established a letterpress-printing house with lithographic and copperplate-printing facilities here. He did this by expanding a workshop for the printing of Prussian banknotes that he had already set up in 1835. For his typefoundry, he purchased matrices of the best French and English roman types. In particular, he offered display types in an unconventionally rich selection. He also had a number of good typefaces cut, especially in gothic and chancellory styles [i.e., the subcategory of blackletter called Kanzlei], as well as some of his own display faces. Haenel had great success with these types, a large percentage of which were cut from Heinrich Ehlert, who went solo in 1858.

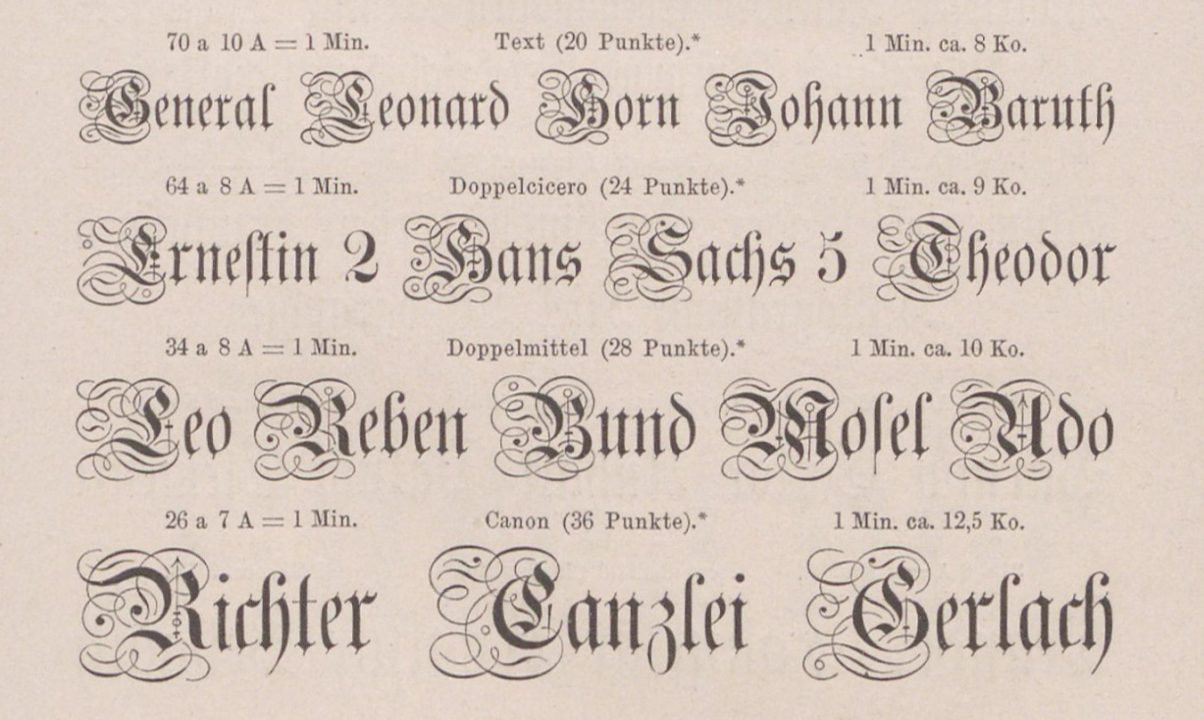

The four largest sizes of the Haenel/Gronau foundry’s Schmale Canzlei, from its 1891 catalog. The typeface is one of at least four in the Kanzlei style to have been cut inside the foundry, although I cannot ascertain whether it came from Heinrich Ehlert’s hands or not.

1845

In 1845, Haenel was the first to introduce the pivotal casting machine to Germany. He had its inventor, the Dane Lauritz Brandt, construct it on his premises, and he delivered Haenel delivered pivotal casters to other typefoundries as well.

1852

On 1 March 1852, Karl David purchased the letterpress, lithographic, and intaglio printing house from von Eduard Haenel as well as the typefoundry, the printers’ ink factory, and the real estate at Lützowerwegstraße 44.[4] He continued the business under the name of Eduard

Haenel’s printing house and typefoundry. The Dessauer Bank was a part-owner.

1856

Eduard Haenel died in Berlin on 16 August 1856.

1864

Karl Wilhelm Gronau, who had been a manager under Haenel and David since 2 January 1852,[5] purchased the business and the real estate from the Bank für Handel und Industrie in Darmstadt on 1 January 1864. He renamed the business Wilhelm Gronaus Buchdruckerei und Schriftgießerei.

Alexander Jürst became a part-owner on 1 May 1864.

1887

Wilhelm Gronau died in 1887. His widow remained a part-owner of the business, which moved to Berlin-Schöneberg in 1896.

1905

In 1905, the printing office split off from the typefoundry and continued operating under the name Gebhardt & Landt GmbH. The typefoundry’s name did not change.

1909

Mrs. Agnes Gronau left the company in 1909, which was thereafter solely maintained by Alexander Jürst.

1918

Commercial councilor[6] Hans Alexander Jürst died on 20 April 1914. Gebr. Klingspor in Offenbach am Main purchased the foundry in 1918.[7]

Schneggenburger & Krumwiede

1833

The punchcutters Schneggenburger & Krumwiede,[8] located at Alte Jakobstraße 5 in Berlin,[9] published an 1833 specimen for a Fette Fraktur in sizes ranging from Petit to Text.[10] In1840, the typefoundry and punchcuttery G. F. Schneggenburger published a quarto-sized specimen.[11]

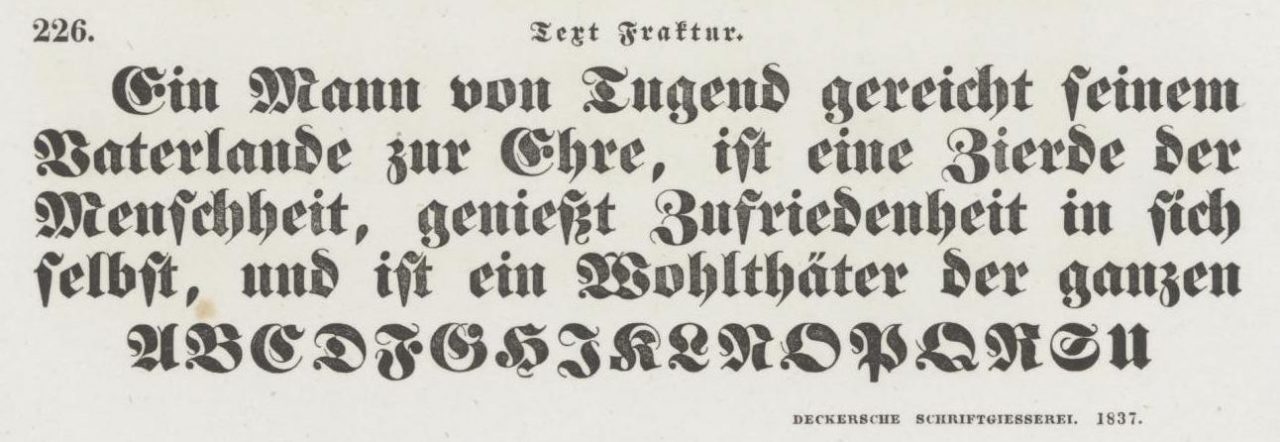

Krumwiede’s Fette Fraktur, in its Text size – i.e., around 20 Didot points. The specimen is a close-up from a page of the 1837 catalog printed for the in-house typefoundry at the Decker printing house in Berlin.

Hayn

1838

In 1838, a typefoundry was operating within the A. W. Hayn printing office, which had been established by Gottfried Hayn in 1798.[12] In 1854, it operated with once casting furnace and two pivotal typecasting machines. It still exists as an in-house foundry.

Beyerhaus

1840

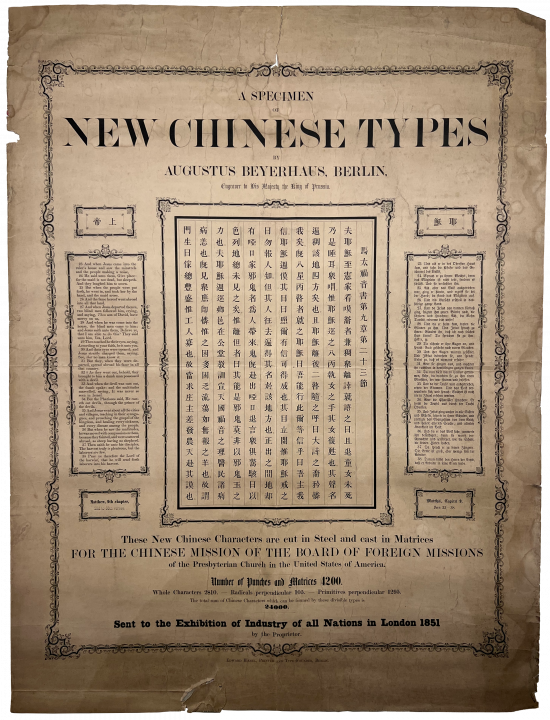

From the typefoundry of A. Beyerhaus, an 1840 specimen of characters from a Chinese typeface is known.[13] These were cut in steel “under the direction of Director-General Dr. von Olfers by A. Beyerhaus in Berlin for the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin and for the missionary Carl Gützlaff in China.”

In addition to standard typefaces, an octavo specimen from this period (1840) has a total of 16 pages showing 165 figures of kaleidoscopic border-printing elements, printed at the office of A.W. Schade.[14]

A specimen of new Chinese types by Augustus Beyerhaus, Berlin, engraver to His Majesty the King of Prussia, 1851. Click to enlarge. The broadsheet was printed for the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London and I shot this terrible photograph of it at the Noord-Hollands-Archief in Haarlem, where it has the inventory number 2487/1767. There is also a copy of this broadsheet at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam. We should all be thankful that the Enschedé printing house and the Tetterode typefoundry preserved such thorough specimen collections over time.

Moeser & Kühn

1842

The W. Moeser & Kühn printing house, established on 2 July 1842, also set up a typefoundry. In 1854, that operated with two casting furnaces and one pivotal caster. Today, it still operates as a dependent foundry within the printing house.[15]

Schoppe

1844

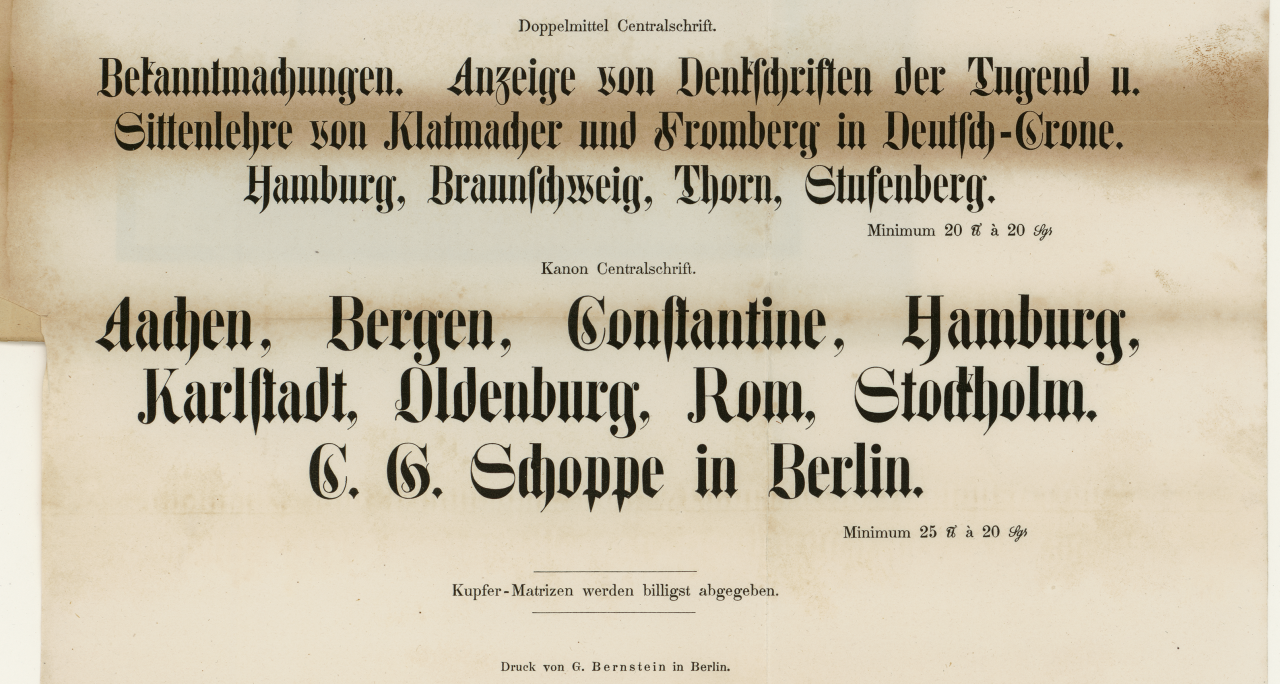

The C. G. Schoppe punchcuttery and typefoundry was established on 1 April 1844 and located in the Dessauer Straße 1. In 1845, it published quarto-sized complete specimen.[16]

1853

In 1853, this foundry published specimens for a “Centralschrift.” The typeface is remarkable – a better term might be odd – for the upper halves of its letters being roman in style, with Fraktur-style lower sides.[17]

Close-up on the two largest sizes of the Centralschrift from »Neueste Proben der Schriftgiesserei und Schriftschneiderei von C. G. Schoppe in Berlin.« Printed by G. Bernstein, it accompanied issue 9 of the Journal für Buchdruckerkunst, Schriftgießerei und die verwandten Fächer in 1853. Photo: Kunstbibliothek der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Photographed by Dietmar Katz.

1854, 1862

In May 1854, Hermann Dehnicke joined as a co-owner; the company changed its name to C. G. Schoppe & Comp. Around this time, it operated with three casting furnaces and two pivotal typecasting machines. Dehnicke left the company on 1 October 1862.

1867

In July 1868, the remaining cast-type inventory was put up for sale at a 50 percent discount. Wilhelm Woellmer took over the foundry in December 1867 and merged with his company.

Theinhardt

1849

In 1849, Ferdinand Theinhardt (born 3 May 3 1820 in Halle an der Saale) established a typefoundry in Berlin. In 1833, Theinhardt had begun an apprenticeship at the old Gollner typefoundry in his hometown of Halle, and he learned typefounding and punchcutting there. After that, he went to Eduard Haenel’s in Berlin before moving to Frankfurt am Main to work for Nies. Returning to Berlin, Theinhardt once again worked at Haenel’s, where he remained until starting his own business in 1849.

1851

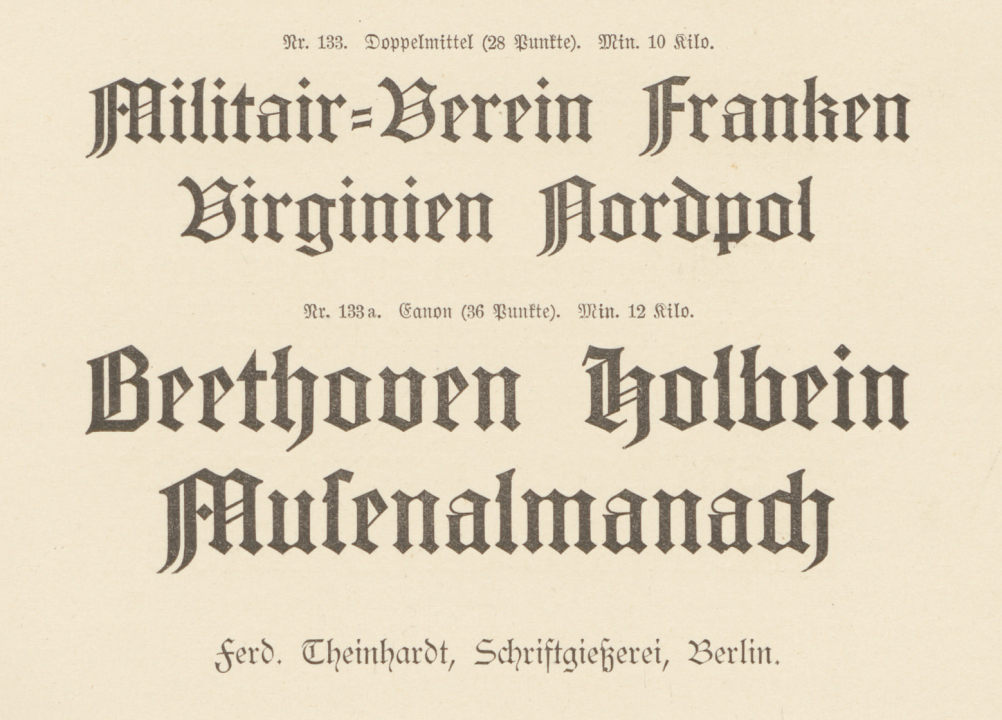

Theinhardt enjoyed his first successes through the cutting and casting of types for government securities. In particular, he supplied the types for the Prussian State Printing Office, established in 1851. He also cut very good Fraktur and roman faces. In 1854, his foundry operated with three casting furnaces.

Since 1851, Theinhardt had cut more than 2,000 hieroglyphic punches for Professor Lepsius;[18] later he cut the punches for Sanskrit, Avestan, Hebrew, and Demotic types – as well as types for other foreign scripts, including cuneiform.[19] For Mommsen’s Corpus inscriptionum latinarum (published from 1863 to 1893),[20] Theinhardt drew and cut seven sizes of Latin-script and two sizes of Greek-scripts types,[21] and Archaic Latin majuscules.[22] The latter[23] were re-released in 1926 by H. Berthold AG under the name “Klassik.”[24]

Also noteworthy is the cut of an “Altdeutsch” modeled on Gutenberg’s textura,[25] which is now distributed by Berthold as “Mainzer Gothisch.”[26] Genzsch & Heyse acquired matrices for the fonts, added larger size that it cut in-house, and then published the package as their “Psalterium” typeface.[27]

Altdeutsch’s 28 and 36 point sizes.

1885

Since his son had died at a young age, Ferdinand Theinhard sold his typefoundry off in 1885. It was purchased by the Mosig brothers and Oskar Mammen.

1906

Ferdinand Theinhardt died in 1906, aged 86. His 1899 biography, Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben, were republished as a bibliophile edition by H. Berthold AG at the end of 1920, commemorating the centenary of his birth.

1908

With the collaboration of the H. Berthold AG, the Ferd. Theinhardt typefoundry was converted into a limited liability company in January 1908. Its shares became the property of H. Berthold AG.

1910

In 1910, the company moved from Schöneberg to Berlin’s Belle-Alliance-Straße 88, where it was merged into H. Berthold AG’s headquarters.[28]

Fickert

1852

The brothers Karl W. E. and Gustav A. L. Fickert (born in 1822 and 1825, respectively) established a typefounding, stereotyping, punchcutting and engraving company under the name Gebrüder Fickert [Fickert Brothers] in Berlin on 1 October 1852. On 1 May 1855, they added a printing business.

In 1854, the foundry operated with three casting furnaces.

1864

In 1864, the typefoundry was given up. Its stores of type and matrices were put up for sale in December 1864.

Notes

- A verschobene Egyptienne is a three-dimensional slab-serif typeface, whose letters appear to be turning on an axis. You can see one on the left-hand (i.e., top half) of this specimen page from a Brno-based printer active in the 1840s.

- In German, »seit 1834 für gemeinschaftliche Rechnung geführte Schrift- und Stereotypen-Gießerei«.

- Two Assman foundry specimens were digitized a few years ago: one from the former Berthold library, and another kept at Berlin’s Kunstbibliothek, which Karl Klingspor donated to one of the library’s predecessor institutions.

- The sale may have been a few days later than this, see note 4 below. Haenel kept his residence, which was located very nearby. His family remained there until 1861; see Paul Enck, »Die Druckerei Hänel«.

- Eduard Haenel made Karl Wilhelm Gronau a manager of the company on 2 January 1850, two years earlier than mentioned in the text. Both Haenel and Gronau surrendered all rights to company management when Karl David purchased the firm on 16 March 1852. David must have re-hired Gronau immediately after that point. An announcement of the sale, signed by Haenel and Gronau, has been digitized by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

- “Commercial councilor,” or Kommerzienrat, was a title given to successful businessmen who had donated considerable funds toward public use. It came with no duties whatsoever, and after the dissolution of the monarchies in Germany, it was no longer awarded – except, for a time, in Bavaria. I have not yet found record of the date Alexander Jürst was honored with this title or what his public works might have been, though I assume they were for members of the printing industries.

- According to a notice in the German government newspaper, Karl and Wilhelm Klingspor’s purchase of the foundry must have been made three years earlier, by 22 January 1915; see Deutscher Reichsanzeiger 1915:57 (9 March 1915), Fünfte Beilage (n. p.).

- Friedrich Bauer’s first edition, Chronik der deutschen Schriftgießereien (1914), included no entry for this foundry.

- I have not the faintest idea where a copy of this, or the 1840 specimen mentioned in the same paragraph, might be kept today.

- Nor have I yet seen a copy of this specimen. For more information about Krunwiede’s Fette Fraktur, please refer to another page on this website, Fette Fraktur questions.

- I do not know if the name change reflected on this 1840 specimen came about because Krumwiede left the business for other terrains, or because he had died in the intervening years. I have not yet seen a copy of this specimen, either,

- Friedrich Bauer’s first edition (note 8 above), did not include an entry for this foundry.

- Bauer’s first edition (note 8 above), did not include an entry for this foundry. I have not been able to locate Beyerhaus’ 1840 specimen of his Chinese typeface. A later specimen of the type is shown as an image above.

- A copy of Beyerhaus’s kaleidoscopic elements is at the Allard Pierson museum in Amsterdam. It is item number 2 from shelf mark OTM: KVB LPF 328 (1–14).

- Bauer’s first edition (note 8 above), did not include an entry for this foundry.

- In Bauer’s first edition (note 8 above), the entry for the Schoppe foundry follows Theinhardt’s foundry, rather than preceding it. He was not yet away of the foundry’s establishment date, not of its 1845 specimen. I have not been able to locate a copy of Schoppe’s initial specimen yet.

- Four sizes of the Centralschrift – Tertia, Text, Doppelmittel, and Kanon – were shown in a supplement to Journal für Buchdruckerkunst, Schriftgießerei und die verwandten Fächer 20, issue 9 (1853). That is the oldest specimen for the typeface that I have yet seen.

- Augustus Beyerhaus – mentioned further above in this post – was the punchcutter initially entrusted to cut Lepsius’s hieroglyph type. I do not know why the project was transferred to Theinhardt. For more information about the resulting face, see this post on their use by the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Today, the hieroglyph punches are maintained by the Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin, and I have some information about them here. Theinhardt prepared a specimen for the face in 1875.

- Like Theinhardt’s specimen for his hieroglyph face mentioned above, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin has digitized his 1877 cuneiform specimen.

- Publication of Corpus inscriptionum latinarum volumes began once again in the twentieth century. Indeed, the project is still ongoing, as you can read on its website.

- Bauer misinterpreted this information slightly. Theinhardt cut six sizes of a Roman inscriptional-lettering style typeface for the Corpus inscriptionum latinarum project. He named this typeface Monumental, and specimen of its six sizes is included in a collection of sheets digitized by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. The next sheet in that volume shows similar-style Greek capitals in two sizes.

- The sheet mentioned above with Theinhardt’s monumental Greek also includes one size of “Archaic” Latin. The name Altlatein seems to me to be a misnomer, however, as stylistically the style of letter used came after the “Trajan”-style letter, not centuries before it.

- Friedrich Bauer made a mistake here. The monumental-lettering-style types that Berthold re-published in the 1920s was not Theinhardt’s Altlatein but six of the classical-style majuscule sizes.

- The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin has digitized Berthold’s specimen brochure for Klassik. Regarding the Monumental/Klassik typeface, see also Charles Maze’s “Three typefaces for Latin epigraphy in France and Germany, 1846–63” on abyme.net.

- An early 1890s catalog from the Ferd. Theinhardt foundry – published after Ferdinand Theinhardt had sold off the business – includes the Altdeutsch typeface. Its largest size is 36 point. A specimen sheet printed after Berthld’s acquisition of the firm in 1908 shows more Altdeutsch sizes – up to 72 point. Based on their product numbers, though, I think that the Ferd. Theinhardt foundry added the fonts, not Berthold after 1908.

- The Berthold-Schriften notebook kept by the foundry after 1900 lists, on page 150, that the Mainzer Gothisch fonts came from the Theinhardt foundry. Berthold’s large catalog, from circa 1911, includes Mainzer Gothisch, too, beginning on page 229.

- A circa 1912 catalog from Genzsch & Heyse shows its instance of the typeface, there named Psalter-Gotisch instead of Psalterium. Page 142 indicates that the 48, 60, and 72 point sizes were cut by Genzsch & Heyse. I cannot yet ascertain whether Theinhardt and Berthold sold Genzsch & Heyse’s added sizes, or cut their own 48, 60, and 72 point additions in parallel.

- Today, Belle-Alliance-Straße 88 is Mehringdam 43 – a landmarked tenement building originally constructed in 1859. Hermann Berthold purchased it in 1869 and over the next several decades, the Berthold factory was built on a plot behind it. To read about Berthold’s 1869–1978 headquarters, see this post.